Microsoft will change the computing world if it integrated its own ARM chips. Almost 50 years ago Intel introduced its Intel 4004. That chip changed computing forever, because it was the first of a long family of processors that, especially with the 1978 Intel 8086, ended up defining personal computing in the following decades.

That processor defined the x86 architecture that has dominated the landscape in PCs and laptops for years, but that dominance is now faltering against the promise of Apple and its M1 chips based on the ARM architecture. So much so that even Microsoft now seems to be designing its own ARM chips, and that’s the best indication that computing might not be what it was very soon.

ARM conquered mobiles first …

ARM was already dominating the mobile market when the first iPhone went on sale: in 2007 98% of mobile devices already had a CPU based on this architecture, but it was the Apple device that caused the explosion of the mobility.

The Cupertino company soon detected how important it was to have its own SoC for its devices: the first iPad of 2010 shone through the integration of Apple’s first SoC, the A4, among other things, and a career that has taken a leap would begin unique with the launch of the Apple M1 for your laptops and desktops.

Along the way, it has been seen how not only Apple, but other manufacturers have opted for their own designs based on ARM’s proposals and have taken advantage of them to conquer part of that attractive segment of mobility.

Qualcomm and MediaTek are great providers in this segment for all those who do not have their own chips, but there have been great technology companies that have also worked on them, and here both Samsung with its Exynos and Huawei with its Kirin are clear examples of that ambition to count. with more and more advanced chips and more adapted to the devices that use them.

All these designs have been during these years destined for mobile devices and also for certain household appliances, but except on rare occasions the ARM chips did not seem able (or wanting) to compete with the microprocessors oriented to PCs and laptops.

Intel and AMD dominated that segment with no problems, and everyone seemed happy with the cast . Neither of them got into the mobility market (too much, although we saw mobiles and tablets with x86 microphones), nor did the others get into (too much, because we have seen ARM laptops and convertibles) into the personal computing segment.

… and now goes for PCs and laptops

The rumble had been sounding for a long time. The processors that Apple integrated into its iPhone and iPad were increasingly powerful and various benchmarks and independent analyzes had made it clear that these ARM SoCs were already as powerful as some x86 processors that we found at that time, especially in ultraportables.

The appearance of a Mac based on one of those chips was inevitable, and the announcement of those teams came this summer, when Apple unveiled the launch of the M1, an SoC that has turned the tables and has demonstrated with its performance and efficiency that this architecture makes (a lot) sense in the PC world that has hardly ever been approached.

Even Qualcomm recognized the relevance of that launch, although without giving the M1 too many compliments. Its president, Cristiano Amon explained that Apple’s chip “validated his belief” that mobile chips can make the leap to the desktop.

Qualcomm has had a few apples in that basket for a long time. Its alliance with Microsoft in the development of ultraportables based on ARM chips with Windows 10 precompiled for this architecture has already borne fruit with products such as the Surface Pro X, but in no case has the proposal of these two giants come close to the one that Apple has shown with the M1.

Microsoft’s challenge is not to design ARM chips, but to solve the limitations of Windows 10 ARM

The impact of the launch of the Apple M1 seems to be provoking the reaction of some giants: these days we knew of the apparent intention – not officially confirmed – of Microsoft to design its own ARM chip. That chip would be especially intended for the servers that it uses in its cloud infrastructure, Azure, but the rumor also made room for a potential version of those chips for its Surface equipment.

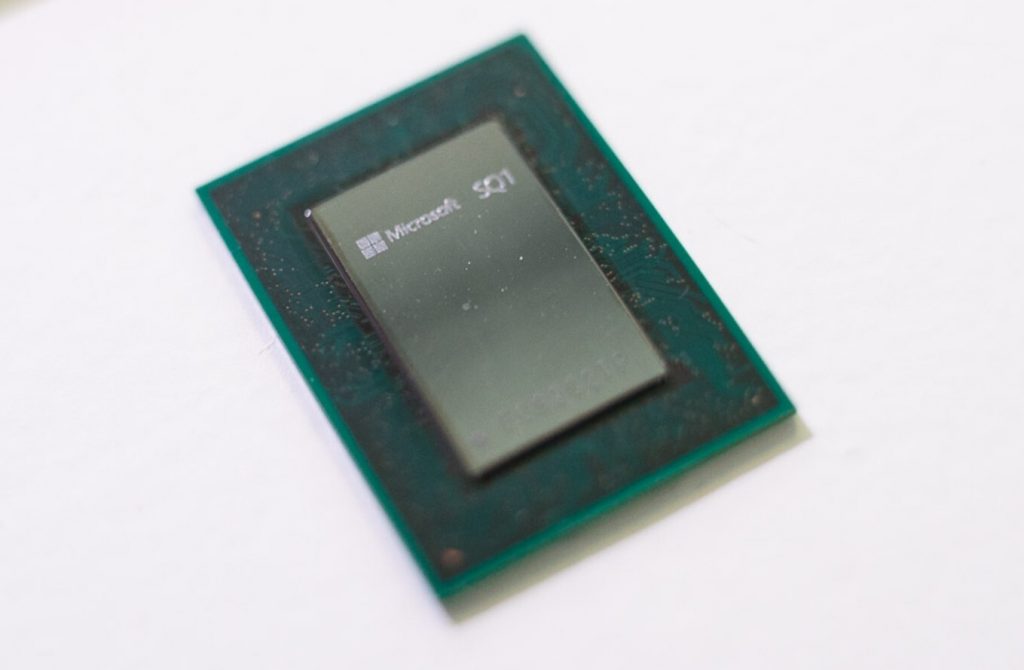

The data is certainly striking, but it clashes with the philosophy of a company that has preferred never to get into those gardens. It is true that it has made small inroads collaborating with semiconductor manufacturers : it has recently done so with the “custom” chips of the Xbox Series S / X in collaboration with AMD or the SQ1 and SQ2 processors of its Surface Pro X.

However, it seems difficult to think of a Microsoft that approaches Apple in that vertical conception and of “total control” of its devices, especially since Microsoft has been working for years with partners that it would probably “betray” by creating its own chip. Therefore, it seems much more reasonable to think that it actually raises these chips for its servers and not so much for equipment that may suppose to compete with partners with whom it has been working for years.

However, we may see some Surface based on those hypothetical chips, without a doubt, and it will be very interesting to see what Microsoft can give of itself in that field, but a priori the problem and the challenge is not that: it is to achieve that Windows 10 and everything your software ecosystem works on these chips as it does on x86 / x86-64 chips.

That has been precisely one of the obstacles that have slowed the advance of the first convertibles based on ARM chips manufactured by Qualcomm. The hardware, without being spectacular, more than fulfilled: the software, no. Among other things due to the inability to emulate x86-64 applications, a limitation that has now begun to be corrected with the latest version of this operating system.

What does Microsoft need here? A scheme like the one proposed by Apple, which has made the “legacy” applications of Intel Macs run (with rare exceptions) on Mac M1s in a transparent way thanks to Rosetta 2. That invisible emulation layer achieves that for the user what’s below the Mac doesn’t matter.

The performance of these legacy applications is lower than that of native applications, but it does not matter because they still work remarkably and that gives developers leeway to prepare native versions for the ‘Apple Silicon’ chips, both the M1 and its successors.

Microsoft should therefore guarantee that transparency that now its Windows 10 ARM does not show. The situation is decent, but it has to improve a lot so that in the end the same thing happens as in current Macs: that it practically does not matter – except in specific cases – if you are using x86 applications or ARM applications.

If Microsoft fixes that problem, we may indeed be ushering in a new era of computing. One in which by the way, Intel – which has long been resting on its laurels – and AMD could be mortally wounded. That, by the way, is another story.